The “Magical” World of Compilers, Linkers, and Loaders

| December 28, 2022

In this blog from O3DE Technical Steering Committee member Jeremy Ong, he goes through the process of compilation and linking used by the MSVC compiler - useful for when you start encountering compilation and linking issues!

Compilers and linkers are not always at the forefront of our minds when we code. At best, we often work off of a vague mental model of how they behave, but while our imperfect intuition might serve us well in many circumstances, not having a more comprehensive view can certainly get us into trouble. It’s possible that our project builds and “works,” but in a way that is suboptimal. Over time, the cumulative inefficiencies of small issues and mistakes made by hundreds of engineers over a growing codebase can add up to become massive workflow problems. If the project you work on or work with exhibits any of the following symptoms, it’s time to take a look at what’s going on in linker-land.

- “I change one line of code in a C++ file and it feels like the whole universe is re-linking”

- “I have dozens of gigabytes of duplicated code in extremely bloated binaries”

- “Attaching a debugger takes forever because the symbol files I’m loading are enormous”

- “I routinely run out of memory while compiling”

The world we all probably want to live in can be described conversely:

- “I change one line of code in a C++ file and I’m up and running quickly. The time it takes to see a change scales with the size and scope of the change.”

- “My binaries can ship on smaller mobile or embedded environments without issue.”

- “My symbol files are manageable, and I don’t experience friction working with a debugger.”

- “Compilation is instantaneous and takes no memory.”

Ok, maybe the last one is out of reach, but you get the idea. Can we achieve this nirvana? Experience shows that we can, but it requires consistent diligence and is the result of a team joint effort. This writeup is intended to get us all up to speed on the knowledge needed to motivate and understand the changes needed for a healthy codebase.

First, we’re going to start from the basics, assuming no prior knowledge of how the C++ toolchain works. Then, we’ll look at some of the things that can go wrong. Finally, we’ll draw some conclusions and try to formalize a set of recommendations about how we should structure our code.

“Hello, world” but with extra steps

Let’s make a simple file to implement the venerable “Hello, World” program, but in a function instead of a main routine.

// hello.cpp

#include <cstdio>

void hello_world()

{

std::printf("Hello, World!\n");

}

On Windows, we can compile this pretty easily like so:

cl.exe hello.cpp /c

The /c option is needed to compile the hello.cpp object file without invoking the linker (which is done by default). The command above produces hello.obj in the same folder. We can verify the contents of the object file with the dumpbin utility:

dumpbin /disasm hello.obj

Running the command above should emit a bunch of assembly code, including instructions associated with printf as well as our hello_world function. Here’s a small snippet:

Dump of file hello.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

?hello_world@@YAXXZ (void __cdecl hello_world(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 8D 0D 00 00 00 lea rcx,[??_C@_0P@DOOKNNID@Hello?0?5world?$CB?6@]

00

0000000000000007: E9 00 00 00 00 jmp printf

Easy enough, we have a simple hello_world function with only a couple instructions. The first lea loads the address of the embedded Hello, World!\n c-string literal for use in the printf subroutine (note that in this particular case, we can invoke jmp directly on the function address, instead of needing to call it as a function).

As it stands, this code isn’t “runnable” in any way. It’s not an executable yet, nor is it in a form that we can load at runtime to execute in the context of another program (i.e. it isn’t a runtime DLL). To do that, we need to use a linker. Let’s first create an executable that invokes our hello_world function.

// main.cpp

void hello_world();

int main()

{

hello_world();

}

If you compile this with cl as above, what do you think should happen? If you aren’t already familiar with the C++ compilation model, you might suspect this would fail to compile - after all, there’s no code defined for what the hello_world function should do when called! However, compiling this with cl /c works just fine and you’ll get a main.obj file for your trouble. Dumping the assembly of that yields:

Dump of file main.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

main:

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: E8 00 00 00 00 call ?hello_world@@YAXXZ

0000000000000009: 33 C0 xor eax,eax

000000000000000B: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

000000000000000F: C3 ret

Note how the function we’re calling is ?hello_world@@YAXXZ, which we’ve actually encountered before in the assembly of our hello.obj file. This correspondence isn’t an accident. When we compiled main.cpp, the compiler had no definition of hello_world when it encountered the call. What it did instead is generate the call instruction for it anyway, with the expectation that at some future time, the address of ?hello_world@@YAXXZ will become resolved. The compiler also makes a record of this unresolved symbol in what is know as the relocations table. Let’s dump the contents of the relocations table using dumpbin /relocations main.obj:

Dump of file main.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

RELOCATIONS #3

Symbol Symbol

Offset Type Applied To Index Name

-------- ---------------- ----------------- -------- ------

00000005 REL32 00000000 9 ?hello_world@@YAXXZ (void __cdecl hello_world(void))

Sure enough, we see that the main.obj file embeds a relocation corresponding to the hello_world function with the matching symbol name. As a quick aside, the symbol name is “just text” and the extra symbols added before and after the function name encode the function’s type declaration. If we declared the function as a C-callable function like extern "C" void hello_world(), the assigned symbol name would simply be hello_world, without the extra decorations.

OK, that’s all well and good, but we still don’t have an executable! We have an object file defining a function, and we have a main entry point that calls that function. We need some way to… link them together, and the tool to do exactly that is the appropriately named linker! Running the command, link main.obj hello.obj /out:hello.exe, yields a hello.exe file which, when run, prints “Hello, World!” The assembly of the main executable is seen below, with the call to hello_world present at the address in bold (0x140001010):

link main.obj hello.obj /out:hello.exe

Dump of file main.exe

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

0000000140001000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000140001004: E8 07 00 00 00 call **0000000140001010**

0000000140001009: 33 C0 xor eax,eax

000000014000100B: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

000000014000100F: C3 ret

**0000000140001010**: 48 8D 0D 09 53 01 lea rcx,[0000000140016320h]

00

0000000140001017: E9 14 00 00 00 jmp 0000000140001030

Linking with extra steps

Armed with the knowledge above, we can imagine how we might compile programs of arbitrary size and complexity. For each C++ file, invoke the compiler to emit its corresponding object file. Afterwards, link all the files together to create an executable.

This “works” but in practice isn’t sufficient due to practical limitations. One problem is that of distribution. If vendor A wants to publish an SDK, it’s inconvenient to provide the SDK in the form of hundreds of thousands of compiled object files, all of which must be linked together with the object files of user code. Add in vendor B, C, and so on, and soon you’ve got a pretty big mess on your hands. It would be nice if each of these vendors could instead link their source files in advance into one larger blob of data to distribute instead, with the expectation that we link against that. Fortunately, this mechanism exists, and the artifact produced by linking a number of object files together is known as a static library.

Let’s make a simple 3 file program to test it out. Two source files A.cpp and B.cpp, define two functions foo and bar, both of which will be called by a third main function. However, instead of linking them all together, we link A.obj and B.obj together into a static library named AB.lib, and then link that with main.obj to create our executable.

// A.cpp

#include <cstdio>

void foo()

{

std::printf("foo\n");

}

// B.cpp

#include <cstdio>

void bar()

{

std::printf("bar\n");

}

// main.cpp

void foo();

void bar();

int main()

{

foo();

bar();

}

As before, each file can be separately compiled into object files via cl /c. Alternatively, we can supply all three files to cl in one go to generate three separate object files via cl /c A.cpp B.cpp main.cpp. If we inspect the relocations of main.obj as before, we should now see two relocations:

Dump of file main.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

RELOCATIONS #3

Symbol Symbol

Offset Type Applied To Index Name

-------- ---------------- ----------------- -------- ------

00000005 REL32 00000000 9 ?foo@@YAXXZ (void __cdecl foo(void))

0000000A REL32 00000000 A ?bar@@YAXXZ (void __cdecl bar(void))

So far we haven’t done anything fundamentally new yet. Let’s now link A.obj and B.obj together to form a static library we’ll call AB.lib with this command: link /lib A.obj B.obj /out:AB.lib. The /lib flag is needed to indicate we want a library, not an executable. (If we omit /lib, link will complain that we haven’t defined a main entry point.)

The dumpbin tool is truly versatile, as it can inspect the contents of AB.lib also! If you use it to dump its assembly, you’ll see code associated with the foo and bar functions as you might expect.

Dump of file AB.lib

File Type: LIBRARY

?bar@@YAXXZ (void __cdecl bar(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: 48 8D 0D 00 00 00 lea rcx,[$SG5198]

00

000000000000000B: E8 00 00 00 00 call printf

0000000000000010: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

0000000000000014: C3 ret

...

?foo@@YAXXZ (void __cdecl foo(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: 48 8D 0D 00 00 00 lea rcx,[$SG5198]

00

000000000000000B: E8 00 00 00 00 call printf

0000000000000010: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

0000000000000014: C3 ret

Now, let’s link the actual executable. The command is similar to the commands we’ve already seen: link AB.lib main.obj /out:ab.exe. Running this produces an ab.exe executable that, when run, emits “foo” and “bar” on separate lines as expected, with both symbols resolved.

This time running with extra steps

Now that we know how static libraries work, are we done now? Well not quite, although we are certainly better off. Now, vendors can distribute SDK binaries in the form of static libraries instead of zillions of object files. However, what if, as a vendor, I want to ship an update to my SDK? If the code in the static library changes, end users would need to relink the entire executable in order to accept the update.

The solution is to leverage not static linking, but dynamic linking instead. As the names imply, “static” linking is done before we run a single instruction, at build time. Dynamic linking however, performs the symbol resolution we’ve already seen at runtime. To see how this works, let’s start with a simple source file that we’ll attempt to link dynamically.

// A.cpp

__declspec(dllexport)

int foo()

{

return 1;

}

The __declspec(dllexport) line is new and needed for dynamic linkage to work. When creating a dynamic library, symbols are not automatically included in the DLL’s export table (we’ll get into this shortly). The dllexport attribute informs the linker, “hey, I want others that use this DLL to be able to use this symbol (function, variable, or class) in their code.”

We can compile and link this file as before if we want, but we’ll use a shorthand which combines cl and link together in one line for brevity: cl A.cpp /link /dll /out:A.dll. Notice that we dropped the /c flag we were using before to avoid invoking the linker automatically. After running this command, we’ll have 4 new files: A.dll, A.lib, A.exp, and A.obj.

If we dump the assembly of A.obj, we should get the expected function body:

Dump of file A.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

?foo@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl foo(void)):

0000000000000000: B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,1

0000000000000005: C3 ret

The assembly of A.dll also has the code above, albeit with another hundred kilobytes or so of additional instructions which we won’t get into:

Dump of file A.dll

File Type: DLL

0000000180001000: B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,1

0000000180001005: C3 ret

0000000180001006: CC int 3

0000000180001007: CC int 3

0000000180001008: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

000000018000100C: 85 D2 test edx,edx

...

However, the A.lib file emitted along with the link command has no assembly at all! We don’t get much output if we use dumpbin /disasm A.lib but we get a different story if we run dumpbin /exports A.lib instead:

Dump of file A.lib

File Type: LIBRARY

Exports

ordinal name

?foo@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl foo(void))

Here, we see that the lib file has the symbol in the exports table. The dllexport attribute is key because without it, not only would this symbol not be present in the exports table, the linker wouldn’t have emitted A.lib and A.exp at all. What’s in the exp file then? Inspecting it, you’ll find that it contains the foo function in its symbol and relocation tables. We’ll circle back to the exp file later, but first, let’s actually use our DLL in the context of an executable.

// main.cpp

#include <cstdio>

// Not optimal, don't do this!

int foo();

int main()

{

std::printf("Version %i\n", foo());

}

Here, we have a main function that invokes foo which is not yet resolved but we know exists in the DLL. To compile this into an executable, we can use the command cl main.cpp A.lib which conveniently links the object file generated from main.cpp and A.lib to produce main.exe. If we run it, main.exe prints “Version 1” to the console as expected, but how? To understand what happened, we can inspect things with

WinDbg , a standalone debugger provided by Microsoft.

[Image: image.png]

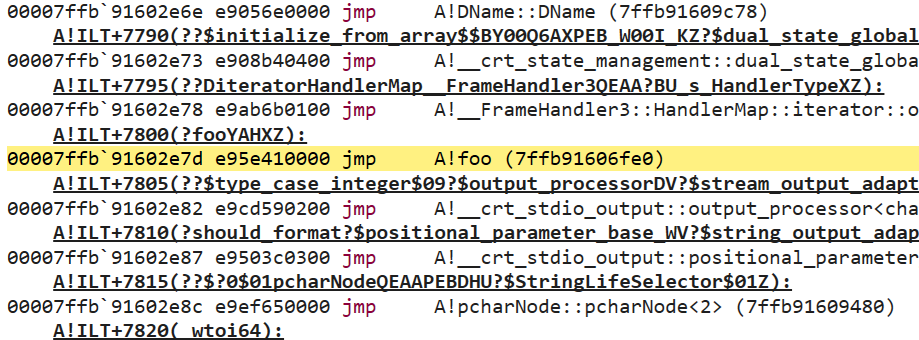

In the screenshot above, we have paused the debugger right after the call to main!foo. Notice that in the bottom left, we have a number of modules loaded, including both our main.exe and also the A.dll library. We didn’t tell Windows to load A.dll, but by linking against its corresponding A.lib import library, the executable had the information needed to do it automatically for us. What did calling main!foo do however? If we inspect its disassembly, it looks like this:

main!foo:

00007ff6`efc371cc ff252e4e0900 jmp qword ptr [main!__imp_?foo@@YAHXZ (7ff6efccc000)]

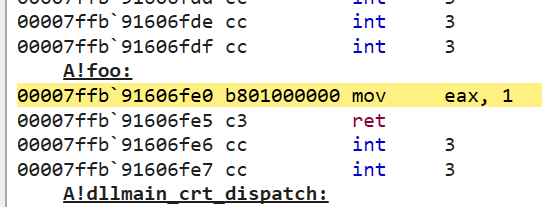

An unconditional jump to __imp_?foo@@YAHXZ! That address is located in the middle of the Import Address Table (IAT) pictured below:

Yet another jump! This time, to something in the A module instead of main. Sure enough, if we step to the next instruction, we wind up at our foo function which we defined in the A.dll module:

Thinking about what this means, after we ran main.exe, Windows was kind enough to load A.dll into memory as well. After doing so, it wrote the address of A!foo into the IAT. When execution called main!foo, the instruction pointer was immediately redirected to the IAT entry corresponding to __imp_?foo, after which it was redirected again to A!foo and we finally arrived at our destination. Phew!

Let’s now do a quick experiment. Remember that our original motivation for embarking on this DLL journey was to be able to modify code in the DLL without needing to relink the main executable and observe the changes.

Let’s change foo in A.cpp to now return 2 instead of 1. After making that change, recompiling A.dll, and not recompiling main.cpp or relinking main.exe, we should be able to run main.exe again and find that it does indeed print “Version 2” instead as expected. This makes sense, after all, the code defined in the body of foo never lived in main in the first place as we have seen.

Optimizing Thunks

The __impl_?foo entry in the IAT we saw before is referred to as an “address thunk” or just a “thunk” for short. Earlier, we saw that when invoking foo from the main function, we did two jumps, first to main!foo, then to __impl_?foo, before finally resolving in A!foo. While the jump from the IAT is needed since this entry is written after the DLL loads at runtime, surely the jump to main!foo is unnecessary. This is where we can correct our declaration of foo to make this optimization:

#include <cstdio>

// Now with the dllimport directive

__declspec(dllimport) int foo();

int main()

{

std::printf("Version %i\n", foo());

}

This is the same as before but with a dllimport directive on foo instead of just a naked int foo() declaration. If we compile this and inspect the disassembly, this is what we should see:

main:

00000001400070C0: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

00000001400070C4: FF 15 36 4F 09 00 call qword ptr [__imp_?foo@@YAHXZ]

00000001400070CA: 8B D0 mov edx,eax

00000001400070CC: 48 8D 0D 4D 6E 07 lea rcx,[14007DF20h]

00

00000001400070D3: E8 18 B4 FF FF call @ILT+5355(printf)

00000001400070D8: 33 C0 xor eax,eax

00000001400070DA: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

00000001400070DE: C3 ret

Notice that we no longer call main!foo and call the function we expect to be written in the IAT immediately. This is great! The reason the compiler couldn’t do this before is because when main.cpp was initially compiled to main.obj, it had no choice but to assume that main!foo would be defined and linked within the same module eventually. As a result, it emitted a call to main!foo. Only later once we linked the import library A.lib did the linker realize “oh, this foo function is actually in a DLL,” at which point it emitted a “trampoline” main!foo function that redirects execution to the IAT.

With the dllimport directive attached to the declaration however, when main.cpp is compiled, we are informing the compiler that “hey, this function is going to come from an external DLL so don’t bother emitting a call for it.” The compiler then prepends the __imp_ prefix and calls the address expected in the corresponding IAT entry immediately. While we are still left with 2 indirection, rendering DLL functions slightly slower (1 to the jump table, then 1 to the DLL), it’s still better than 3.

Running with even MOAR extra steps

We now have a mechanism by which we can change code without recompiling or relinking other modules that are dependent on that code, mostly! The mechanism described so far is referred to as “implicit dynamic linking,” and is “implicit” because the runtime resolves the DLL function address thunk on our behalf. This required us to manually export the function from the DLL, and then link against the import lib from the dependent module.

As it turns out, there’s a way to load a DLL, query a function pointer, and then call it without needing to either export the function or link against the import lib. To demonstrate this, we’ll use the following code in two source files:

// A.cpp

__declspec(dllexport)

int foo()

{

return 1;

}

// main.cpp

#include <Windows.h>

#include <cstdio>

// Not a declaration of a function, but a type declaration

// with a matching signature

typedef int (*foo_t)();

int main()

{

HMODULE A = LoadLibrary(TEXT("A.dll"));

if (A != NULL)

{

// THIS WON'T WORK YET!

foo_t f = (foo_t)GetProcAddress(A, "foo");

if (f)

{

std::printf("Version %i\n", f());

}

else

{

std::printf("Failed to retrieve function pointer\n");

}

FreeLibrary(A);

}

else

{

std::printf("Failed to load A.dll: %u\n", GetLastError());

}

}

If we compile a DLL for A.cpp with cl A.cpp /link /dll, the compiler emits A.obj, A.dll, and the lib and exp files we got before. However, when we compile our executable this time around, we’re no longer need to link against A.lib because cl main.cpp will compile main.obj and links it into main.exe in one go.

The main function is more complicated now because we are explicitly loading the DLL and getting the address to the function instead of letting the vcruntime do it for us. If we run main.exe as written above however, we’ll get the error “Failed to retrieve function pointer” printed. What gives?

As before, we can examine functions exported from the DLL with dumpbin. Running dumpbin /exports A.dll yields the following output:

Dump of file A.dll

File Type: DLL

Section contains the following exports for A.dll

00000000 characteristics

FFFFFFFF time date stamp

0.00 version

1 ordinal base

1 number of functions

1 number of names

ordinal hint RVA name

1 0 00002E7D ?foo@@YAHXZ = @ILT+7800(?foo@@YAHXZ)

The name of the function isn’t foo, it’s… ?foo@@YAHXZ. Sure enough, changing the call to GetProcAddress to request ?foo@@YAHXZ instead of foo will print Version 1 as expected. The other thing we could have done is defined foo in an extern "C" block in A.dll to disable name mangling since we aren’t using argument-dependent lookup (ADL). We can also verify at this point that if we change foo to return 2 and recompile just A.dll and run main.exe again, it prints Version 2. No re-link of main.exe needed!

Linking static libs to DLLs, static libs to static libs, DLLs to DLLs, DLLs to static libs

So far, we’ve only linked static and dynamic libraries directly into an executable. However, we can link libraries to other libraries as well in pretty much every configuration you can imagine. Furthermore, we can have libraries depend on DLLs either implicitly, or explicitly, which in turn could have other dependencies also.

If it isn’t clear already, this can get messy really fast. Let’s look at a few motivating examples to see what can happen, starting first with a really simple case of linking A.lib with B.dll and main.exe.

// A.cpp (-> A.lib)

int foo() { return 1; }

// B.cpp (-> B.dll)

int foo();

__declspec(dllexport)

int bar() { return 1 + foo(); }

// main.cpp (will link A.lib and B.lib)

#include <cstdio>

int foo();

__declspec(dllimport)

int bar();

int main()

{

std::printf("%i\n", foo() + bar());

}

From A.cpp, we make a static library using cl /c A.cpp and link /lib A.obj as before. From B.cpp, we make a DLL that links A.lib via cl B.cpp /link /dll A.lib. Finally, we create our executable using cl main.cpp /link A.lib B.lib. Running main.exe at this point should print the expected output 3 - it works!

So what’s the issue then? Well, “technically” there is no issue, but this is not the best way to structure things as we shall see. It’s also worth first trying to understand how this worked at all. If we dump the assembly of A.lib, we see the following:

Dump of file A.lib

File Type: LIBRARY

?foo@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl foo(void)):

0000000000000000: B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,1

0000000000000005: C3 ret

If we dump the assembly of B.dll on the other hand, we see this:

Dump of file B.dll

File Type: DLL

0000000180001000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000180001004: E8 07 00 00 00 call **0000000180001010**

0000000180001009: FF C0 inc eax

000000018000100B: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

000000018000100F: C3 ret

**0000000180001010**: B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,1

0000000180001015: C3 ret

The call to the emphasized address 0000000180001010 drops us just a few lines below where we should recognize the code corresponding to foo. Because foo itself wasn’t exported by B.dll, it’s code just lives as part of the B module on top of the A module. Finally, let’s look at the assembly of the executable itself with dumpbin /disasm main.exe /out:main.asm:

Dump of file main.exe

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

0000000140001000: 48 83 EC 38 sub rsp,38h

0000000140001004: E8 E7 00 00 00 call **00000001400010F0**

0000000140001009: 89 44 24 20 mov dword ptr [rsp+20h],eax

000000014000100D: FF 15 ED 4F 01 00 call qword ptr [**0000000140016000**h]

0000000140001013: 8B 4C 24 20 mov ecx,dword ptr [rsp+20h]

0000000140001017: 03 C8 add ecx,eax

0000000140001019: 8B C1 mov eax,ecx

000000014000101B: 8B D0 mov edx,eax

000000014000101D: 48 8D 0D 0C 53 01 lea rcx,[0000000140016330h]

00

0000000140001024: E8 67 00 00 00 call 0000000140001090

0000000140001029: 33 C0 xor eax,eax

000000014000102B: 48 83 C4 38 add rsp,38h

000000014000102F: C3 ret

...

**00000001400010F0**: B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,1

00000001400010F5: C3 ret

...

The addresses for calling foo and bar are emphasized here. The first call to foo is visible since it sets eax to 1 and returns again. To verify that the second highlighted address takes us to the bar thunk, we can dump the imports of main using dumpbin /imports main.exe:

Dump of file main.exe

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

Section contains the following imports:

B.dll

**140016000** Import Address Table

14001FC28 Import Name Table

0 time date stamp

0 Index of first forwarder reference

0 ?bar@@YAHXZ

We haven’t done this yet, but we could have also done this before with our first implicit linking example. We can see that the IAT for B.dll resides at address 140016000 and contains a single entry which matches our call in the assembly of main.exe above.

This means that the compiled code used to implement foo exists in at least four places on disk and twice in memory. On disk, the compiled code for foo is replicated across A.obj, A.lib, B.dll, and main.exe since all three modules invoke foo. In memory, it exists in main.exe but also in B.dll which is implicitly loaded at runtime. This isn’t good for a few reasons. First, if there was a lot more code associated with A.lib, we’re consuming a lot of disk and memory to link this library everywhere. The consumption scales linearly with the number of dependents on A.lib. Second, at runtime, the code for foo will be duplicated in each module that invokes it. If we had C.dll, D.dll, and more, each linking against A.lib and each calling foo, the code needed to execute foo is duplicated in each of those DLL address spaces. As for why that duplication isn’t good, while it’s true that the instructions themselves take up memory, another issue is that repeatedly invoking this function in different modules thrashes the instruction cache (often abbreviated as I$), despite the code for foo being identical in each module. Third, this mode of compilation creates a workflow problem as well. If we change code in A.lib, all dependent modules (exes, libs, DLLs) need to relink A.lib, which in a sizable project can drastically hamper iteration times.

A better pattern in this case would have been one of the following options:

- Link everything statically

- Link everything dynamically

In both cases, the code associated with foo would only exist in one location in memory at runtime. In the static-link-everything case, the code would only exist twice on disk, once in the object file, and once in the final executable (unless we compiled intermediate library targets along the way, in which case we duplicate it once per intermediate). In memory, foo would have been resident only in the final executable image. Alternatively, if we compiled everything as DLLs, the code for foo would exist on disk exactly twice (once in A.obj, and once in A.dll) even if A.dll was depended on by many other DLLs and executables. Furthermore, at runtime the code for foo would only exist in the address space of A.dll. An important caveat of the reduction in storage required for DLLs is the implication: having the code reside in a single location means that if the DLL is in use, attempting to recompile the DLL will fail since the vcruntime holds a writer lock on the DLL itself. A common mitigation of this is to stage a copy of the DLL into the final location to permit recompilation while the copy is in use.

One Definition Rule

Most C++ engineers are familiar with the notion of ODR (the One Definition Rule). Officially, Wikipedia offers a nice summary of the rule in 3 stipulations:

- In any translation unit, a template, type, function, or object can have no more than one definition. Some of these can have any number of declarations. A definition provides an instance.

- In the entire program, an object or non-inline function cannot have more than one definition; if an object or function is used, it must have exactly one definition. You can declare an object or function that is never used, in which case you don’t have to provide a definition. In no event can there be more than one definition.

- Some things, like types, templates, and extern inline functions, can be defined in more than one translation unit. For a given entity, each definition must have the same sequence of tokens. Non-extern objects and functions in different translation units are different entities, even if their names and types are the same.

Delving into every edge case and mechanism used to detect ODR violations or resolve possible ODR violations before they occur is well outside the scope of this writing, but I still wanted to give one example of how this can play out in practice.

// A.cpp

template <int S>

int X() {

return S;

}

int foo() {

return 1 + X<2>();

}

// B.cpp

template <int S>

int X() {

return S;

}

int bar() {

return 2 + X<2>();

}

// main.cpp

#include <cstdio>

int foo();

int bar();

int main()

{

std::printf("%i %i\n", foo(), bar());

}

Here, A.cpp and B.cpp both instantiate the template function X<2>. In this demo, we’ll compile A.cpp and B.cpp and link them together to make AB.lib via cl /c A.cpp B.cpp and link /lib A.obj B.obj /out:AB.lib. Finally, we’ll link AB.lib with the main object file to create the final executable via cl main.cpp /link AB.lib. Running main.exe should print “3 4” as expected.

Well, how did that work? If we look at the assembly of A.obj, B.obj, and AB.lib, we see the following:

Dump of file A.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

?foo@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl foo(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: E8 00 00 00 00 call **??$X@$01@@YAHXZ**

0000000000000009: FF C0 inc eax

000000000000000B: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

000000000000000F: C3 ret

**??****$X@$01@@YAHXZ** (int __cdecl X<2>(void)):

0000000000000000: B8 02 00 00 00 mov eax,2

0000000000000005: C3 ret

Dump of file B.obj

File Type: COFF OBJECT

?bar@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl bar(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: E8 00 00 00 00 call **??$X@$01@@YAHXZ**

0000000000000009: 83 C0 02 add eax,2

000000000000000C: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

0000000000000010: C3 ret

**??****$X@$01@@YAHXZ** (int __cdecl X<2>(void)):

0000000000000000: B8 02 00 00 00 mov eax,2

0000000000000005: C3 ret

Dump of file AB.lib

File Type: LIBRARY

?bar@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl bar(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: E8 00 00 00 00 call **??$X@$01@@YAHXZ**

0000000000000009: 83 C0 02 add eax,2

000000000000000C: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

0000000000000010: C3 ret

**??****$X@$01@@YAHXZ** (int __cdecl X<2>(void)):

0000000000000000: B8 02 00 00 00 mov eax,2

0000000000000005: C3 ret

?foo@@YAHXZ (int __cdecl foo(void)):

0000000000000000: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000000000004: E8 00 00 00 00 call ??$X@$01@@YAHXZ

0000000000000009: FF C0 inc eax

000000000000000B: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

000000000000000F: C3 ret

**??****$X@$01@@YAHXZ** (int __cdecl X<2>(void)):

0000000000000000: B8 02 00 00 00 mov eax,2

0000000000000005: C3 ret

By my count, the code associated with int X<2>() shows up 4 times here, once per object file, and then twice in the static library. As it turns out, the static library just concatenates all the sections of its inputs since it isn’t part of an executable module or DLL just yet - relocations haven’t yet been performed. The main.exe assembly on the other hand looks like this:

Dump of file main.exe

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

0000000140001000: 48 83 EC 38 sub rsp,38h

0000000140001004: E8 07 01 00 00 call 0000000140001110

0000000140001009: 89 44 24 20 mov dword ptr [rsp+20h],eax

000000014000100D: E8 DE 00 00 00 call 00000001400010F0

0000000140001012: 8B 4C 24 20 mov ecx,dword ptr [rsp+20h]

0000000140001016: 44 8B C1 mov r8d,ecx

0000000140001019: 8B D0 mov edx,eax

000000014000101B: 48 8D 0D FE 52 01 lea rcx,[0000000140016320h]

00

0000000140001022: E8 69 00 00 00 call 0000000140001090

0000000140001027: 33 C0 xor eax,eax

0000000140001029: 48 83 C4 38 add rsp,38h

000000014000102D: C3 ret

...

00000001400010F0: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

00000001400010F4: E8 07 00 00 00 call 0000000140001100

00000001400010F9: FF C0 inc eax

00000001400010FB: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

00000001400010FF: C3 ret

0000000140001100: B8 02 00 00 00 mov eax,2

0000000140001105: C3 ret

...

0000000140001110: 48 83 EC 28 sub rsp,28h

0000000140001114: E8 E7 FF FF FF call 0000000140001100

0000000140001119: 83 C0 02 add eax,2

000000014000111C: 48 83 C4 28 add rsp,28h

I’ve highlighted corresponding addresses but essentially, we first call bar, which then calls X<2> and later we call foo which then calls X<2> also. Crucially, the orange address there corresponding to the instruction mov eax,2 is the code associated with our template function.

The point of this demo is to demonstrate a few things. First, the template template <int> void X() doesn’t show up anywhere here. If we use dumpbin /relocations and dumpbin /symbols on all our compiled artifacts, we’ll only see instead the specialization of the template. This is because templates, on their own, don’t have a corresponding symbol and associated code. They only become code once instantiated, which in this case happens twice in A.cpp and B.cpp. The second observation is that the data above demonstrates why this pattern isn’t an ODR violation. The way compilers operate are that they happily emit code for each definition seen and instantiate templates for each object file, even if the same instantiation is needed in other object files within the module. Only at the link stage does the linker realize “oh hey, I have duplicate entries here, let’s just take one of them.” If we have a hefty template that is used all over the place, we pay the cost to compile that template instantiation all over the place too. This cost is paid in compute time, space on disk, extra link time, and more. Templates are critical in many cases, but keeping them lean is critical to managing healthy compile and link times. This advice applies just as much to inline functions declared in a header.

Reader beware! With ODR, the linker will generally try to help us out where possible. If within a single module or compilation unit, a symbol is defined multiple times, you will likely get a compiler or linker error (depending on the toolchain you use). This is also true if you use strictly static linking and combine multiple libraries together with symbol collisions. With dynamic libraries however, collisions in symbols exported across different DLLs don’t result in a build-time linker error. This can result in weird situations, with some modules calling a different implementation of a function than you expect. Beware of symbol collision across DLL boundaries!

Where does CMake fit into all of this (and MSBuild, Ninja, Make, etc.)

So far, we’ve been manually invoking the compiler and linker commands that ship with the Visual C++ toolchain from Microsoft. Of course, the command-line executables and flags that ship with Clang, GCC, and other compilers are different. In addition, above we’ve manually had to track what needed to be rebuilt after making changes. Build systems generally do the dependency tracking for us, so we can change code freely and expect all dependencies to recompile and relink as necessary. Because build systems have a perfect understanding of the dependency graph, they can also parallelize the build, leveraging as many available system resources as you permit.

CMake even abstracts the build systems themselves, so that dependencies are respected and users have an abstract interface to specify target types (static library, dynamic/shared library, executable, virtual), declare dependencies between them, and of course, associate source files with targets if any.

Let’s do a quick test to see if CMake’s handling of DLLs operates as expected. We’ll go with a very simple scheme, one DLL linked into one executable (using sample code you’re probably sick of by now).

// A.cpp

__declspec(dllexport)

int foo() { return 1; }

// main.cpp

#include <cstdio>

__declspec(dllimport)

int foo();

int main() { std::printf("%i\n", foo()); }

Instead of compiling these files and linking by hand, let’s use CMake :

# CMakeLists.txt

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.24)

project(DLLDemo)

add_library(A SHARED A.cpp)

add_executable(main)

target_link_library(main PRIVATE A)

After generating the project with cmake . and invoking the build using cmake --build ., we’ll get a Debug folder (default configuration) with our various artifacts inside, including A.dll, A.exp, A.lib, and main.exe as we’ve seen before! Without making any changes, we can confirm that cmake --build . does not rebuild anything (check file write timestamps).

Furthermore, if we change the implementation of foo, we should find that A.dll and its PDB updates, but not the import/export files! This is a critical optimization that allows us to update the code in A.dll without needing to relink and re-emit its dependencies. However, if we add or remove dllexport symbols from A.dll, we should find that the lib/exp files are updated along with the DLL, and furthermore, the main.exe executable needs to relink. In other words, with implicit linking, dependents only need to update when the exported interface changes, not the implementation. Great! It should be easy to verify that if A was compiled as a static library instead (the default), changes to the implementation would have necessitated a relink.

Recommendations and what to learn next

Armed with the mental model above, you should be able to look at a dependency graph of libraries, source files, and executables and reason about:

- What symbols are being exported by whom?

- What code duplication is there?

- If I make a change to a source file, what needs to rebuild?

If there was a single takeaway, it should be that excessively mixing static and dynamic linkage is an anti-pattern. The exception being the case of implicit dynamic linkage, where the static import lib serves only to define DLL dependencies and entries in the IAT.

The next reasonable question to ask is, “when should I use static linkage, and when should I use dynamic linkage?” Static linkage is typically the code you want to ship with. It removes the need to issue many mmap calls to the kernel to map each DLL’s address space into memory. It also removes the import address indirection which adds overhead to each function call that crosses a DLL boundary. During development however, it’s preferable to primarily use dynamic linkage. The built-in indirection means that in many cases, modifying code and rebuilding its DLL will not require any additional compiling or relinking of dependent modules. A mechanism to swap linkage type based on the build type exists already in O3DE based on whether we are in “monolithic” build mode (“monolithic” refers to the shipping release). However, it’s unfortunately very easy in our build system to hardcode STATIC or SHARED targets and dependencies to them. To sidestep the issue of duplicate code/symbol emission, a common pattern in the engine is for each Gem to define static targets that are only used internally within the Gem to enforce that they are only linked against once, typically by a target that can be compiled as a DLL to expose the Gem’s public interface.

What about explicit DLL loading? This should really be used in cases where a module depends only on a stable subset of the API of another module (which it loads explicitly). This way, the module doing the explicit loading never needs to recompile, even if the DLL interface changes along with its import lib (since it never needed to link the import lib in the first place). Another reason to consider explicit DLL loading is when dealing with external code which doesn’t provide an import lib at all (common with driver code, graphics APIs, etc.). For drivers in particular, it’s common for drivers to update when the operating system updates, and it would be inconvenient for the user to need to update all their software at the same time. With explicit DLL loading, driver updates (and updates of any explicitly loaded DLL) can happen without any changes to the dependent software. Finally, the classical reason to consider explicit DLL loading is if you want to support unloading and reloading the DLL at runtime (and querying the proc addresses again) to support hot-code reloading.

Phew! While this was a long-ish write-up, as with most things in computer science and engineering, it really is only scratching the surface. We didn’t talk about executable formats, ASLR (address space layout randomization), RIP-relative addressing (how ASLR is handled on Linux), the GOT (global offset table), platform differences between Windows, Linux, and MacOS, DLLs shared across multiple processes, DLLMain entry points, exported symbols that aren’t functions, what the point of the exp file even was (i.e. how it’s used to resolve circular dependencies), and a whole host of other topics. For each topic of interest, hopefully, you’re equipped with the relevant background to find what you need and continue learning. To my knowledge, there isn’t a great comprehensive resource that includes all of the above, but if you find it (or write it), let others know! With that, hopefully you find the magical world of compilers, linkers, and loaders, just slightly less magical.